Book Review: El Vino de Cocos en la Nueva España by Paulina Machuca

Book Review: El Vino de Cocos en la Nueva España: Historia de una Transculturación en el Siglo XVII by Paulina Machuca. El Colegio de Michoacán A.C. (2018).

Paulina Machuca’s El Vino de Cocos en la Nueva España is a landmark work that should be read by all serious students of Mexican spirits. Machuca’s monumental archival research and lucid prose make for a tour de force, telling the little-known story of vino de cocos. This distillate was brought to America by Filipinos and was, Machuca argues, the direct predecessor to mezcal. That latter point is perhaps the most interesting one to the average agave fan and reader of this blog, though it forms a short coda to the book as a whole. El Vino de Cocos traces the course of the coconut palm from its ancient origins in India, to the Philippines, and all the way to what is now Mexico via the Galeón de Manila, beginning in 1565.

Reportedly only 500 copies of the book were printed and it has not been translated into English. So I will use this space to provide more of a summary for Anglophone readers outside of Mexico than a traditional book review.

Coconuts do not typically inspire the type of fascination that agave does. However, Machuca’s first chapter vividly illustrates that they should. In exactly the same way that agave (the “tree of wonders” to Spanish colonists) met most of the basic needs of Mesoamericans, coco palms (the “tree of life” for people throughout southern Asia) provided food, shelter, clothing, tools, medicine, vinegar, and beverages, including alcoholic ones. Mildly alcoholic tuba made by fermenting fresh palm sap is consumed to this day in both the Philippines and Mexico. Distilled tuba would become known as vino de cocos in New Spain. It would quickly become a serious competitor to pulque, wine, and ultimately midwife the birth of mezcal. Then, it would disappear just as suddenly.

The American epicenter of this distilling tradition was Colima, today the capital of a small coastal state of the same name. An ancient Purépecha trade route through Pátzcuaro connected Colima and its vino de cocos with Mexico City. Another route through Guadalajara facilitated the spirit’s delivery to mining areas throughout New Galicia, and all the way to what is now Chihuahua. Over a century before mezcal was produced in the village of Tequila, “Colima” was used as an eponym for vino de cocos by northern miners who had never seen a palm tree. Machuca points out that this is likely the earliest use of Denomination of Origin-like nomenclature in Mexico.

Los indios chinos

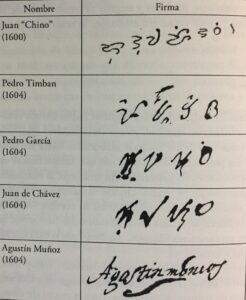

Machuca evokes a vivid multicultural world of seventeenth century Colima from dry archival documents like court proceedings and tax records. Using evidence unearthed in Mexico, Spain, and the Philippines, she rightly foregrounds the “indios chinos” as the protagonists of this story. The indios chinos were mostly Filipinos, but this clumsy appellation was applied to all manner of indigenous Asians under the Spanish caste system. These sailors and indentured servants brought to America generations worth of knowledge about myriad uses of the coco palm, including the distilled spirit they called lambanog. Their place in colonial social structure was complicated: some were pushed into chattel slavery, while others became affluent landowners. For most of the century, the procurement of tuba and vino de cocos was the exclusive domain of Asians, whether as exploited laborers or rural capitalists. Coco palm haciendas sprung up along the Pacific coast, and indio chino know-how was imperative for the production of booze. Climbing a towering palm to extract tuba was to “subir de chino,” and regional prejudices led many to assume that all Asians knew how to distill!

Vino de cocos in historical context

Domestic alcohol production had been prohibited in New Spain in 1545, when its consumption by Indians, Blacks, and slaves was also made illegal. The Crown and Church would rely on three classes of arguments for intermittent prohibitions over the centuries: that drinking caused social disorder and immorality, that it (and pulque in particular) led to pre-Christian religious idolatry, and that its consumption cut into Spanish wine tax revenue.

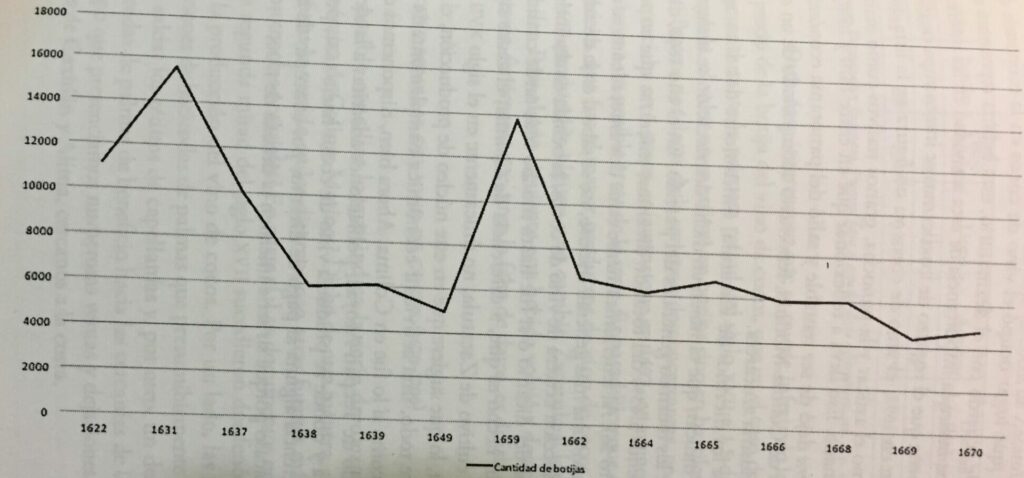

Nevertheless, vino de cocos was being produced in Colima by 1609 at the very latest. There were 60 productive tabernas in the village by the following year, and by 1622 the region was distilling nearly 200,000 liters annually from tens of thousands of palm trees. Vino was one of the three most important industries around Colima, trailing cacao and cattle. Local authorities successfully lobbied for a dispensation to legalize it in 1627, and a boom in production and sales ensued. Four years later, the Church would be reaping over half of all tithes in Colima from distillers.

This boom would be short-lived however, and production would decrease greatly once the government in Guadalajara obtained a monopoly on liquor distribution and set prices that were beyond the reach of most consumers. Production plummeted by two thirds, bottoming out in 1649. A smaller, second peak occurred after state distribution was scrapped and prices fell in 1659. But by 1670, the party was over. Increased competition from cheaper spirits produced closer to inland markets (including mezcal), the lure of cash crops like vanilla and rice, a re-invigorated prohibitionist policy, and the declining profits of coastal haciendas led to the rapid demise of the vino de cocos industry. The last documented batch was sent to Zacatecas in 1704. After nearly a century of glory, the spirit ceased to exist in Mexico.

Trade routes and the roots of mezcal

During its heyday, vino de cocos was popular in mining towns throughout modern day Jalisco, Michoacán, Guanajuato, Zacatecas, Durango, and San Luís Potosí. It is no coincidence that mezcal production would become endemic along these routes beginning in the mid-seventeenth century. Machuca addresses the possibility of pre-Hispanic distillation delicately, but is unequivocal in her argument that mezcal in occidental Mexico evolved from the vino de cocos tradition.

Machuca summarizes the history of the pre-Colombian distillation hypothesis from Carl Lumholz (in 1904) to that currently proposed by Zizumbo and Colunga. She points out that no affirmative proof for distillation (as opposed to fermentation) has been offered, and that otherwise exhaustive chroniclers of the early colonial period do not mention native distillates.

One of the juiciest parts of this book is Machuca’s unearthing of a quote about mezcal from 1616, indicating that it had recently come on the scene. (This is a full five years before the oft-quoted Lázaro de Arregui reference to mezcal.1) An official is arguing that a novel spirit is escaping the mandatory tithes, namely a

“…vino that was introduced in these parts a few years ago, made from plants called maguey and mezcal… from which a valuable, profitable and healthy vino is made…so Spaniards and Indians alike are planting said mezcales and magueyes on their land…making said vino to drink and sell…this category is still not subject to tithing since it has not been around for long.”

(p. 354, my translation)

In contrast, Machuca’s archival research reveals that the first explicit reference to mezcal in Oaxaca does not occur until 1777!

The appearance of mezcal shortly after the arrival of vino de cocos is no coincidence. As indigenous people gradually took over vino de cocos production from the declining and assimilated Asian population, distillation techniques spread like wildfire along the trade routes. Suddenly, rural communities throughout the west could use free local materials to produce mezcal for consumption or sale in the mining areas. In contrast, Colima’s famous liquor could only be produced near the coast, had relatively high material and labor costs, and had to be transported through regions where bribes were obligatory. Machuca claims definitively that vino de cocos birthed mezcal. If so, the child matured fast and took its parent’s life.

The scope and achievements of this book are impressive, and the criticism offered here is mild. For some readers, the book may at times bog down in archival detail. For serious scholars however, that will be a strength. I was left with one nagging question that the book failed to answer, though. Why does tuba continue to be produced and consumed in Colima over three centuries after vino de cocos disappeared? Given her profound knowledge of the subject matter, I would have loved to hear Machuca’s thoughts about this.

Ultimately, this is a superb and important work of scholarship. I cannot recommend it highly enough for readers of Spanish. Machuca delves into the techniques of tuba and vino production, the indios chinos’ social roles and caste position, prohibition, and the economics of it all, in great detail. It is at the same time one of the most accessible academic texts you will find. Its originality, quality of research and clarity of expression make it a mandatory reading for anyone seriously interested in the history of Mexican spirits.

1 “…they extract a must from which they make a wine from cactus sap, distilling it clearer than water and stronger than spirits.” Domingo Lázaro de Arregui, “Descripción de la Nueva Galicia” (1621). Reprinted by Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1946. Felisa Rogers translation.