My New Favorite Tequila – That Isn’t a Tequila

My new favorite tequila isn’t really a tequila, legally. It was made by a man whose family has been making tequila for centuries longer than laws defining tequila have existed. With that disclaimer out of the way, I’ll be calling this blue agave distillate “tequila” and “vino” interchangeably, following local custom. I’ve recently spent much more money than I can afford in order to sponsor a six-metric ton batch of this juice. I did this not as an investment or to start a brand, but because I saw an opportunity to directly participate in preserving part of tequila’s original culture. The story starts around two years ago.

The plain glass bottle had a handwritten label hung with string around its neck. “Alfredo Ríos Landeros – Atemanica,” it read. It was some of the best tequila I had ever tasted. This was sometime in 2017, and my neighbor in Tequila, Jalisco brought me the bottle as a gift. I wanted to meet this Alfredo character, and get some more of his delicious vino. After tracking him down, he explained that this was the last batch he had made (over two years prior), and that he wouldn’t be able to make more until the price of blue agave (then at 10 pesos/kilo, now at 30 pesos/kilo) came back down to earth.

Over the following twenty months, Alfredo and I would get to know each other a bit, and eventually make plans to get him some agave to work with. I asked him if the tequila he produced would be as good as what I had tasted. He said that, while he couldn’t guarantee any particular volume, if I found mature agave with good sugar levels, the juice would be as tasty as any he had ever made. That was good enough for me.

Atemanica, La Sierra de Tequila

For as long as I’ve known the town of Tequila, locals have spoken of “la sierra” in reverential tones. To hear tequilenses tell it, people in the sierra live in a state of somewhat primitive purity – compared to Valley folk, they are more decent, harder working, prouder, and very mistrustful of outsiders. Many in Tequila have family in the sierra, and they will advise you that it’s a bad idea to head into those mountains without an invitation. It was a hotbed of revolutionary activity during the Cristero War, and has an outlaw reputation that survives to this day.

The pueblo of Atemanica, at 1,237 meters above sea level in the Sierra de Tequila, has about 300 inhabitants. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was the administrative and political capital of Tequila, due to its important silver mines. While the area has been famous for its quality distillate for centuries, local tavernas were completely clandestine until 1994. Previously, they were frequently destroyed by colonial gendarmes, revolutionaries, and the modern Mexican military.

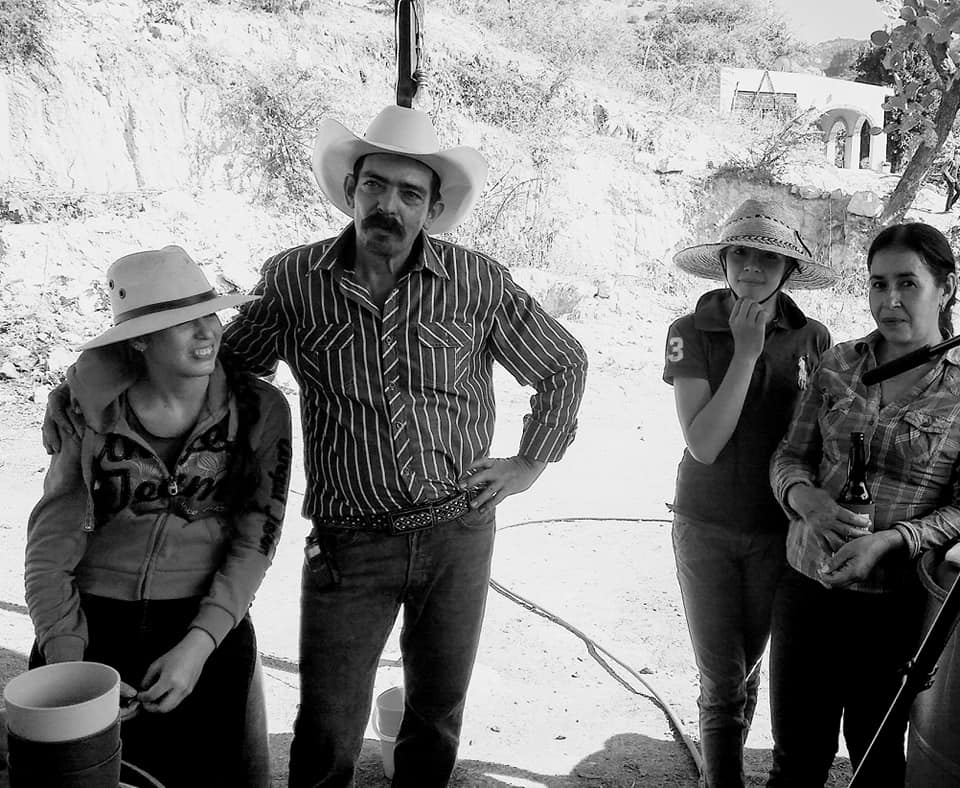

Alfredo learned to make tequila from their father “from the time [he] could carry heavy loads” – starting at about age 15. The family tradition of distilling goes back at least as far as Alfredo’s great grandfather, who was the original owner of the copper pot alembic he uses today. As Alfredo and his brothers grew up and started their own families, they began building their own individual tavernas. They all remember a time when agave was free, and they quickly sold all of the tequila they could make, sending it up into neighboring Zacatecas via mule trains.

The Agave

Alfredo tells me that his father always told he and his brothers “Plant agave, don’t be lazy!” “But,” he continues, “we didn’t pay attention, and now we’re paying the consequences.”

With help from the Banuelos family (producers of Mezcal Los Potrillos), I found mature, six-year old blue agave for sale in Tesasalco, Zacatecas. Alfredo and I drove out there before committing to the purchase, as I wanted his approval for any agave I was going to buy. The Brix levels were good, and he smiled brightly when he told me this was “muy, muy buen mezcal.” The agave was just over the Jalisco state line, meaning it is outside of the Denomination of Origin for Tequila. Even so, the rest of the agave in that field was headed to a well known tequila distillery in the Jalisco Highlands. Such is the state of tequila today.

The Process

The agave arrived in Atemanica just before Christmas. Alfredo cooked it 36 hours in a brick oven, with steam provided by his wood-fired boiler. He let the cooked mezcal cool and rest for three days, then milled it with a mechanical shredder, powered by an old tractor motor. He then filled five 1,000 liter plastic vats with the shredded, cooked agave fiber.

He added warm water, and this is where things get really interesting. Alfredo still practices the traditional batida, in which the maestro tavernero disrobes and gets into the fermentation vat, further rendering the agave fiber, and arranging it in a uniform layer atop the watery agave juice.

Fermentation was completely ambient – absolutely no yeast was added. With chilly mountain temperatures in December and January, it took 13 days for the first vat to be ready to distill.

Alfredo has a single, 600 liter, copper pot alembic, elegantly held together with copper clips, an indicator that it is over a century old, pre-dating the widespread availability of bolts and machined parts in Mexico. The still is heated directly with firewood. First distillation is with fiber, and no cuts are made. The ordinario is distilled a second time, making a small heads cut and a much larger tails cut. We ended up making two distinct tails cuts, for two different versions of the final distillate: one at 44% alcohol by volume, and one at 41% ABV.

What’s Next?

Alfredo was ecstatic to have agave to work with after several years, and his entire family’s pride was evident. I asked him if he’s interested in doing another batch soon. He said, “we’re ready to work hard, to make a better life for ourselves. God willing there will be work. We need work. Not just for me, but we hope for work so that something greater will come for all of us. To make more tequila for you güeros up there, so you can enjoy it from time to time.”

This blue agave distillate cannot legally be sold, but I have almost 400 liters of it, and am happy to facilitate tastings of it in Mexico or the United States. (I will be including it in a tasting at the Mexico in a Bottle events in San Diego and Dallas, in March and May, 2020.) I will also be continuing this modest community development project with Alfredo and his family. In addition to putting together enough money for another batch before the rainy season begins, our goal is to raise funds to help Alfredo begin re-building his wooden fermentation vats, as he’d like to move away from the cheaper plastic that has been an economic necessity.

To organize a tasting, make a donation, or volunteer to edit video of the process, please contact me here.